One maneuver scary to many student pilots is The Stall. This maneuver comes in a variety of flavors—there is the power off stall, the power on stall, the approach to landing stall, the accelerated stall. It is no surprise this is scary for new pilots.

When we talk of “stalls” to initiates, we have to be careful to explain it has nothing to do with the engine quitting. So many inexperienced pilots believe when a flight instructor or another pilot mentions the term, “stall,” it has something to do with engine failure.

Engine failure is a completely different topic I will talk about later, but for now, all you new pilots or would-be pilots need to know when a pilot talks about stalls, it has to do with the wing’s ability to produce lift. It has nothing to do with the engine.

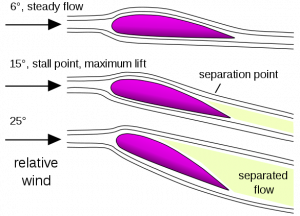

When we speak of a wing stalling, we are referring to the smooth airflow of the wind across the top and bottom of the wing. The wing has to “cut” through the air fairly well straight ahead for the wing to produce the lift required for the airplane to fly. If the pilot increases the “angle” the wing is cutting through the air too much, then the airflow over the wing is disturbed.

Should this happen, the wing “stalls” and can no longer produce the lift required for the airplane to “fly.” Now don’t be alarmed, this sounds worse than it actually is—at the moment the stall happens, the airplane quits flying and begins falling out of the sky.

While “falling out of the sky” seems awful to the uninitiated, it really is not. Here is something you have to keep in mind: when the wing is stalled, it can instantly be “unstalled” (properly referred to as recovered) simply by releasing the “backpressure” on the stick, yoke, or wheel on which you are pulling back.

The moment you release the stick allowing the elevators to come down, this lowers the nose, which immediately decreases the angle of the wing as it slices through the air. The instant this happens, the wing is “flying” again.

Now, for the technical terms—the angle of wing slicing through the air is known as the angle-of-attack (AoA); the wind the airplane is flying through and passing over and under the wing is known as the relative wind; the angle of the nose relative to the horizon is the pitch attitude; and the speed with which the relative wind passes the aircraft is airspeed.

For you flight instructors out there teaching, this is really one of the most important points to keep in mind. When you introduce stalls to your student, you need to do so slowly and gently… What do I mean?

For one, allow your student to realize the stall and stall recovery has nothing to do with engine power. You can do this by introducing power off stalls with recovery simply by controlling the AoA. Few instructors do this because the book talks about “applying full power to minimize the loss of altitude on the recovery.” This in itself is a scary phrase for a new pilot to read or hear. However, let me ask you this: does a glider pilot apply full power on stall recovery?

No, of course not. He or she will lower the nose (decreasing the AoA) to get the glider flying again. It has nothing to do with engine power. This is something you should introduce to your students at the outset of training.

This alone will allow the student to associate the importance of decreasing the AoA to get the aircraft flying again.

Another thing you have focus on is the kinesthetic. Students have to understand there is no extreme dropping off, or falling out of control, or anything else that scary. One of the things I do to help explain and demonstrate to students that the pilot is in full control of the airplane, is to go to a relatively high altitude, reduce power to idle, and stall the airplane’s wing.

Then I will sit there with the stick full back keeping the wings level with the use of rudder. As we come down, I release the backpressure or pitch, the airplane starts flying immediately, and then I slowly pull the nose up again into another stall.

I do this repeatedly to emphasize to the student that you can still control the airplane regardless of what is happening with the wing. In other words, you can control the AoA of the wing and choose when it flies and when you want it stalled.

Flying is, of course, all about control.

-30-

© 2011 J. Clark

“Flying, is of course, all about control.” Unfortunately, so is marriage. When that does become the reality it is time to bail out. Or get a new co-pilot.

Pingback: Teaching Stalls, Part I (via joeclarksblog.com) « Calgary Recreational and Ultralight Flying Club