My last blog was about the men who saved England, no, indeed the world. The documentary I watched about the pilots who flew in the Battle of Britain moved me. Their story overwhelmingly impressed me because of my realization of what the pilots went through during this time. For the first time, I had an inkling of what it must have felt like to be one of the Spitfire pilots fighting off an enemy that outnumbered friendly forces by a factor of 12 to one, or more. Having been in the sky in a tactical airplane dogfighting others, I knew what it was like, to a degree. But the story of the pilots who flew in the Battle of Britain made me realize combat today could not compare to aerial dogfighting of yesteryear.

(Found at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m0-fVLCnsBs.)

If you travel to a Naval Air Station, or an Air Force base, or run into a bunch of Marines fighting Harriers or Hornets, they will tell you they are fighter pilots. Others will point to them and say, “There are the fighter pilots.” And yes, they are fighter pilots, there is no question about it.

However, the pilots of the RAF and RCAF who defended Britain against the Germans during the summer of 1940 are the epitome of fighter pilots.

Winston Churchill spoke of the courage and tenacity of the British and Canadian fighter pilots. On August 16, 1940, Churchill was visiting the Battle of Britain Bunker at RAF Uxbridge to witness the operations of the No. 11 Group RAF Operations Room. When leaving the facility, Churchill looked at Major General Hastings Ismay and said, “Don’t speak to me, I have never been so moved.” Several minutes of silence passed and then Churchill added, “Never in the field of human conflict has so much been owed by so many to so few.”

The sentiment would become central to the speech he would deliver four days later to the House of Commons on August 20, 1940.

Later, I spoke with a few pilots and some non-fliers who did not know the story of John Gillespie Magee, Jr., or what he had done to become famous. McGee’s story is a fascinating, albeit, short story.

McGee’s father, John Gillespie McGee, Sr., came from an affluent family in Pittsburgh. Rather than staying in Pittsburgh, the elder McGee chose a life as a priest in the Episcopal Church. He became a missionary and worked in Nanking, China. While in China, he met and married his wife, Faith Emmeline Backhouse, of Helmingham, Suffolk, England. On June 9, 1922, the couple had a son, John Junior, in Shanghai, China.

McGee’s education started at the American school in Nanking, China. Later, while his father continued his work in China, John and his mother returned to England. His education in England continued until 1939, at which time he chose to visit the United States. By the end of the summer in 1939, it was time for Magee to return to school in England. With the start of the war in England, this was not possible. Consequently, he finished his education in the United States.

While going to school in Connecticut, he competed for and won a scholarship and entrance into Yale University. He chose, however, to do his duty for England; he traveled to Canada enlisting in the Royal Canadian Air Force. After joining the RCAF in October 1940, McGee began flight training right away. Assigned to the No. 9 Elementary Flying Training School at RCAF Station St. Catharines in Ontario, he first learned the basics of flying in the biplanes of the training squadron – yellow Fleet Finches.

The typical amount of training in the Fleet Finch included about 55 to 65 hours. After completing basic flight training, the cadets moved onto the Canadian’s Harvard, which, in America, was known as the T-6 to Army cadets and as the SNJ to naval aviation cadets.

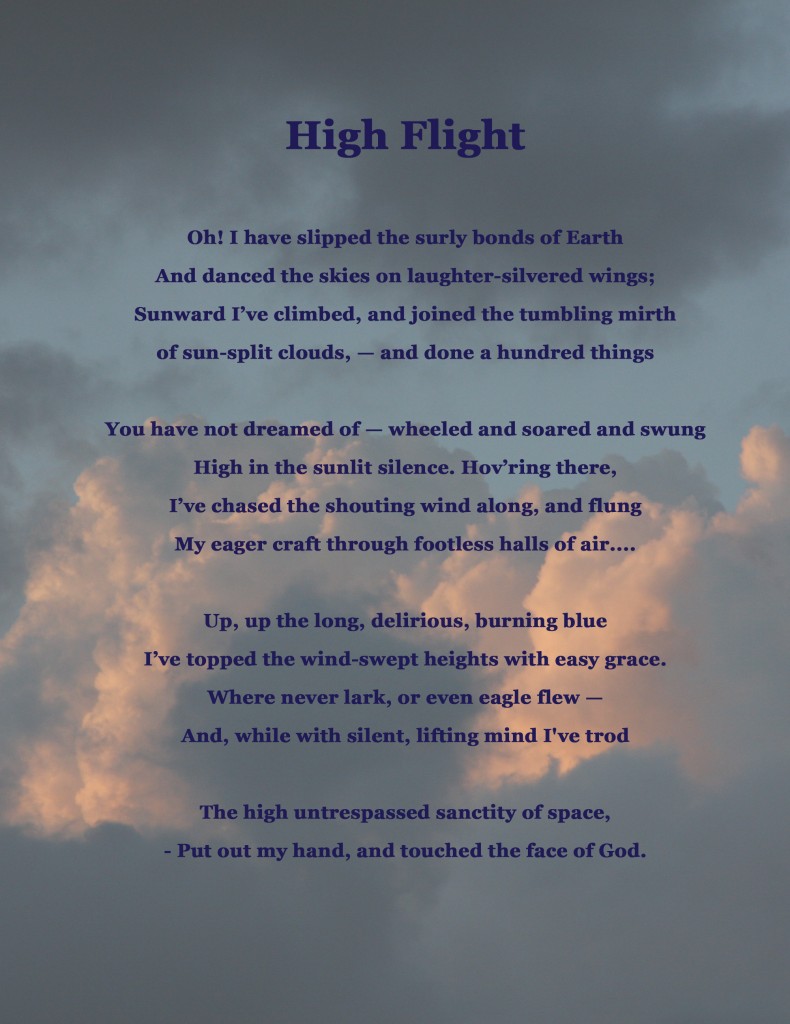

After he finished training with No. 2 SFTS in Ottawa, the RCAF sent McGee to England where he would learn to fly the Supermarine Spitfire with No. 53 Operational Training Unit (OTU) of the RAF station at Llandow, in Wales. It was while assigned to the No. 53 squadron that Magee wrote his famous poem, “High Flight.”

The genesis of the poem followed a flight in a Spitfire up to altitudes above 33,000 feet. While up there among the high clouds over England, McGee was moved by his thoughts and by what he saw at the high flight levels. When he landed later that afternoon, he wrote his now famous poem.

High Flight is a favorite sonnet among aviators and astronauts. Many have used the poem in part and in whole in several other literary works, the movies, at funerals, and more. Cadets at the Air Force Academy must memorize the poem in its entirety. It is the official poem of the Royal Canadian Air Force. The first person ever to read his poem was one of McGee’s fellow pilots at the No. 53. Pilot Officer Michael Le Bas would later go on to become the commanding officer of the No. 1 Group of the Royal Air Force and later serve as Vice Air Marshal.

Later, McGee mailed the poem to his parents in Washington, DC. At the time, John McGee Sr. was serving with St. John’s Episcopal Church and he reprinted the poem in church publications. High Flight was then included in an exhibition of poems called “Faith and Freedom,” which went on display at the Library of Congress in early 1942. Today, the original poem resides at the Library of Congress.

After concluding his transition training into the Spitfire, McGee took orders to No. 412 (Fighter) Squadron, of the Royal Canadian Air Force. RAF Station Digby, England served as the unit’s home station. McGee began flying combat missions in the Spitfire over England in November 1941.

On December 11, 1941, McGee was on a training flight with two other members of his squadron. The three-ship formation was descending down through clouds when they broke out at about 1500 feet. Just below the cloud bases, cruised an Airspeed Oxford trainer from Cranwell. McGee’s Spitfire hit the trainer. There was later testimony that Magee actually rolled back the canopy, stood up in the cockpit and tried to parachute to safety. Unfortunately, he was too low and he and the Oxford pilot died.

Pilot Officer McGee was only 19 years old at the time.

-30-

©2012 J. Clark

Note: Email subscribers, please go to my blog to view vids

Pingback: 80 Years Young | joeclarksblog.com