One of the great perils of flying is weather. Particularly in the early part of the last century, weather was extremely hazardous. When the weather went “down,” flying became dangerous. It was dangerous because aviators were incapable of landing on instruments at the time. Why? No one had invented the instruments or techniques for landing blind.

The story behind instrument flight development is very interesting and the names of those involved in making instrument flying possible are familiar to modern day aviators. Harry and Daniel Guggenheim, Jimmy Doolittle, Elmer Sperry Jr., Paul Kollsman, Benjamin Kelsey, Jack Dalton, and Bill Brown comprised some of the members of the team which made the accomplishment of blind-flying a reality.

The Guggenheim’s contribution was primarily financial. Daniel Guggenheim, along with his wife Florence, created the Daniel and Florence Guggenheim Foundation which they formed to promote many charitable causes. They created their wealth from the mining industry in the late 1800s and believed in giving back to the society which allowed them to be successful.

Their son, Harry, served in the Navy during World War I during which time, he further developed his interest in aviation. After the war Harry became involved in other aspects of aviation. In the latter part of the 1920s, he and his family through the Guggenheim Foundation, contributed $2.6 million in aviation related programs. One of those programs involved the development of instrument flight.

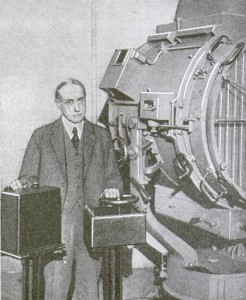

The Guggenheim Foundation created the Full Flight Laboratory at Mitchell Field, Long Island, NY. At the laboratory, a team created from military personnel and the aviation industry worked together to solve the problems of instrument flight. Paul Kollsman developed the sensitive altimetry instruments, Elmer Sperry and his company perfected the gyroscopic instruments, and Corporal Jack Dalton of the U.S. Army took care of the mechanical readiness of the NY–2 aircraft. Bill Brown of MIT provide technical assistance. This group of professionals worked tirelessly for the 11 months prior to the first blind flight experimenting with and developing the instruments making the flight possible.

Jimmy Doolittle and Ben Kelsey, both Army Air Corps pilots, would fly the NY–2 in a demonstration of total blind-flying. At first, Doolittle wanted to fly the demonstration solo; Harry Guggenheim insisted Kelsey be added as a safety pilot to avoid mid-air collisions.

On September 24, 1929 Doolittle and Kelsey took off from Mitchell Field in the NY–2 shortly after ten o’clock in the morning. Sitting in the rear cockpit underneath a canvas canopy, Doolittle was completely blind to the outside world. He would effect a takeoff, a climb to altitude, and fly a rectangular pattern. The plan was for him to navigate around the pattern on instruments using magnetic headings and a stop watch. His next task was to align the aircraft on a final approach using a short-range radio beacon system.

Finally, Doolittle was to land on the same field from which he took off – without ever seeing the ground.

During the entire flight Kelsey sat in front cockpit holding on to the sides of the cowling with his arms outstretched. His was probably one of the hardest jobs during the whole experiment.

While Doolittle and the team at the Full Flight Laboratory proved instrument flying was possible, it would be another five years before instrument flight became practical.

Today, it is something we merely take for granted.

-30-

© 2010 J. Clark

Pingback: Amazing Transportation | joeclarksblog.com