Want to be one of those pilots your friends and family will always want to fly with? Want repeat customers all the time? How do you do that? Well, you have to be smooth and one area in which smoothest really counts in getting the airplane down from altitude.

If you are one of those pilots who yanks the power back and “screams” down from cruise altitude, no one is going to want to fly with you again, include your engine.

By reducing power drastically and somewhat “diving” down, what you are doing is “shock-cooling” your cylinders. This will lead to cracking and very expensive engine repairs.

Proper planning for the descent is almost as important as planning fuel reserves. This area of flight planning is one pilots tend to ignore and one that provides great returns on investment regarding lower operating costs. It boils down to how you treat your airplane; treat it well, it will never let you down. However, if you abuse it, well, as they say . . . stand by.

If you are cruising at 7500 feet at a nominal cruise speed if 100 knots, you can use a 300 fpm descent profile to get down. Planning that descent takes a little finesse that goes beyond just checking out the charts in the book.

There are more reasons than one why a 300 fpm is beneficial. First, an easy descent provides my passengers the greatest comfort with regard to ear-popping pressure changes. Almost anyone can handle 300 fpm.

When it comes time for the descent, you need only adjust the elevator trim down slightly. You do not reduce the power. The airplane will accelerate slightly, but the more important part of the procedure is that power stays on the engine allowing for constant cylinder head temperatures. The big trick to this procedure is planning the point at which to start the descent.

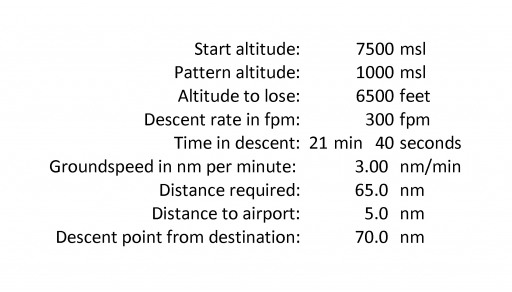

Assuming you want to be near pattern altitude about five miles from the airport to decelerate to pattern speed, your equation for let down planning will look something like this:

Forty-one miles away for the descent point is quite a distance. Keep in mind that is for an old, stodgy Cessna. If you fly something sportier such as an RV-7 or Mooney, look at the numbers for those airplanes that cruise roughly 180 knots, or three miles per minute.

You can run the equation for different altitudes and airspeeds and the results are going to be typically surprising. It takes quite a bit of planning and real estate to get an airplane down from altitude.

Instrument pilots are quick to point out that ATC expects pilots to descend “as rapidly as possible” to within 1,000 feet of the target altitude and then at 500 fpm. While this is true, there are ways “to play the game” so that you get what you want. The tool for this is “pilot’s discretion.”

At your predetermined descent point, simply request a descent at pilot’s discretion. Once the controller grants the request, you can descend at 300 fpm to the limit altitude. You may get clearance all the way to your requested altitude, or not. If you are limited to a higher altitude than requested, simply give them a couple of minutes lead by requesting a further descent when you are 600 feet above the newly assigned altitude. Typically, controllers can work with pilots with these types of requests.

By maintaining power and keeping engine temperatures constant, you can avoid costly trips to the maintenance hangar. More importantly, your passengers will thoroughly enjoy the ride.

-30-

© 2010 J. Clark